1

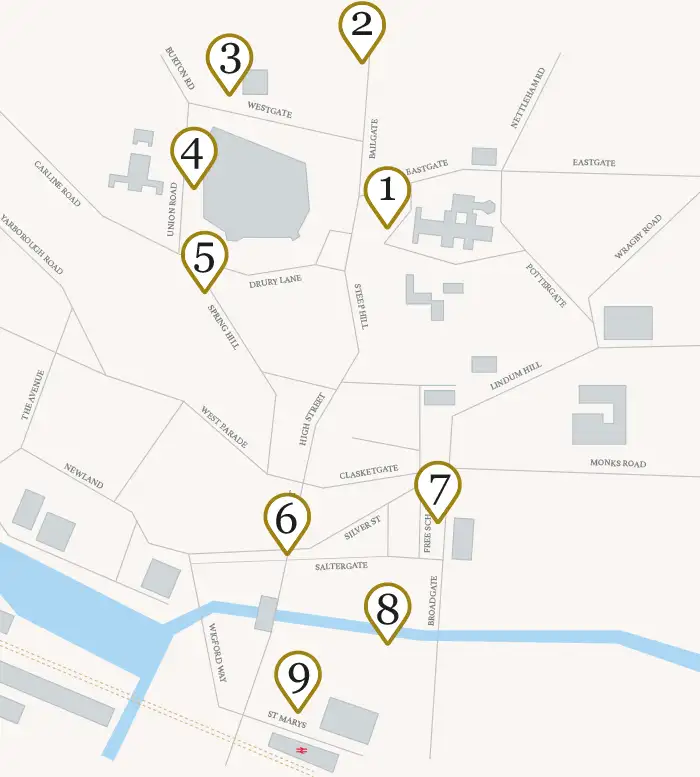

Start in Castle Square looking through the Exchequer Gate

arches towards the Cathedral, and then walk into Cathedral

Close.

Gilbert’s first article describes activity one early morning in Castle Square. He passes under the Exchequer Gate arch to examine the Cathedral and its Close. Gilbert was from a chapel-going family, and his account betrays his mixed feelings towards the Cathedral, the Anglican Church, and its clergy!

There is no one about, at least no one knows you, to distract attention. Those who are out are hurrying to work, and the Castle-square is uninhabited, except for the pigeons. Very bold they are too — you can nearly pick them up. A man at the corner was feeding them this morning whilst a little girl tried to ring a bell, and he told me they belong to the Bishop, “or at least they sleep there. We feed them,” he added, quite unnecessarily, taking the bell from the child, who could hardly raise it, and bringing, with a few sharp stokes, a cloud of wings about his head. They all seem of one colour — I don’t know if it is natural selection working protectively, for their dull-grey bodies are almost invisible against stone walls and cobbles of the Square.

Pondering the question I passed through the archway, coming into the warm sunlight to take a fore-shortened squint at the west front of the Cathedral. We mustn’t be vandals, of course, but if that arch would fall down, what a view there would be from the Square! If only the Suffragettes would be useful now... But it would be built again even higher!

The houses around (the Close I believe) looked more secluded and forbidding than ever. Their fronts hold aloof, and they seem discreet and proper and long dead, except where a yellow curtain peered forth like a primrose. Do these Cathedral dwellings take their looks from their inhabitants, or is it the other way round? Probably the former, I thought, and could picture myself as most reserved if I lived here. With a sniff of disdain I went along to the left. Yet — who knows — perhaps I wrong them. Maybe they have gardens behind, with fruit trees on old stone walls, and cats asleep on jolly lawns.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Outside the Minster’, Lincolnshire Echo, 26 March 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Outside the Minster’, Lincolnshire Echo, 26 March 1914.

2

Return to Castle Square, and then walk along the left-hand side of Bailgate up to its junction with Westgate. Look out for the line of circles of light-coloured cobble stones, and where they finish.

Gilbert recalls walking along Bailgate and starting to encounter ‘mysterious’ circular stones set into the street and pavement surfaces. He thought they might be old Saxon millstones being put to new purpose. Puzzled, he steps into a local bakery and asks. Gilbert shows his stronger appreciation of some periods of history than others!

“This is a curious thing,” said I, and striding over the double one, I passed along, counting them as I walked, to find myself bearing towards the left hand, until at last I came to stand right on the pavement, where, sunk in the stone slab, were three, all interwoven. This was surely the climax! I looked, and, lo, a baker’s shop! The last signs were at his doorstep, and all was clear. It was an advertisement in stone — an early English joke (heavy, of course), a trail leading straight to business...

But why should they cease where they did, at the beginning of the trail? If they ran to the Castle Square, now, one could understand; but they didn’t, and I could see no light unless they originally led past a rival bake-house to keep people on the right path... In I went, to find out what could be learned of this enterprising Saxon advertisement. “What is the meaning of these millstones, down the road?” I asked, pointing through the open door.

“Millstones? Oh, yes. Those are the stones marking the foundations of the pillars at the entrance to the Roman Baths,” said he, leaning over the counter. ‘They curve away here; and when we rebuilt a wall, behind the house, we discovered others.”

He gave me a number of details, being a kindly soul and one evidently interested in the matter; indeed he made me ashamed of the slighting way that I thought of the Romans... The Saxons, after all were a reactionary gang and left no monuments behind. Even Stonehenge is British. But, on the other hand, they left their fierce spirit — or did they? Is there anything of it left? I wonder.

The Roman Baths must have been a considerable affair!

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The Mysterious Millstones’, Lincolnshire Echo, 16 April 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The Mysterious Millstones’, Lincolnshire Echo, 16 April 1914.

3

Walk along the right-hand side of Westgate, passing the Castle to your left, and onto the Water Tower. Look out in the grounds a wall plaque recalling a local Typhoid epidemic.

Gilbert visited the Water Tower on a warm day. It had been built to resolve failings in the city’s water supply. This had culminated in a typhoid epidemic and a tragic loss of lives. Gilbert expressed his faith in progress, and stressed the importance of local civic leaders keeping up better with the needs of a growing city!

I climbed the stairway — a hundred and sixty-nine steps there were, winding round and round until the tank was reached. It’s something like a tank, too! No wonder the walls are massive! But I soon tired of peering into it, because after its magnitude has amazed you, it is no more of a spectacle than a water butt at home; so up I went on to the roof to feast upon the view...

After descending I walked around the grounds with the Engineer. “Shall you stand a dry summer?” I asked. ‘Oh yes,” said he. ‘We can do it without bothering ourselves. Yesterday was a record day — they used over a million and a half gallons!” I didn’t wonder at that, because the day itself had seemed to me a record one. The sight of the swimming bath, was peculiarly grateful in the heat, and I shall look forward this summer to pleasant plunges before breakfast. The whole of the grounds are well laid out, and I take my hat off to those who have undertaken the task.

The tower is a symbol of more than water. It challenges the Castle and Cathedral in more ways than one; for it is a token of the new spirit. We still build Castles, or what is the modern equivalent in Dreadnoughts, and occasionally we achieve a new Minster, but our faith is in the future instead of the past.

It isn’t all faith and hope, however. We can no longer, in cities, play hazard with our share. Lincoln has had a sharp lesson, and her wounds are hardly healed. It is well that these pipes should bear the fountain of life to our lips instead of a darker cup, which they offered in that terrible time. Long may the guardians of Lincoln stand as securely as this tower.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The Water Tower’, Lincolnshire Echo, 4 June 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The Water Tower’, Lincolnshire Echo, 4 June 1914.

4

Continue to the end of Westgate, and walk along to left-hand side of Union Road. Make your way through the west entrance of the Castle, crossing the moat, and into the central castle courtyard.

At the Castle, Gilbert reflected on times past, and which buildings should be saved. Gilbert would have approved of the preservation of the Castle and the opening-up of its grounds as a public park. However, he felt that the ‘old’ gaol and ‘obnoxious’ red-brick courthouse within stood for historic injustices and should be destroyed!

I stopped one morning to watch some men at work upon a row of cottages and seeing a door ajar in a hoarding, peeped through to discover — the Castle Moat... Before any houses were built at all — either cottages to the north and west, or mansions to the south and east — the Castle must have been a splendid spectacle, for its mound is high, its banks are steep, and the walls commanding.

The week following my discovery, a controversy began in the Press about these cottages, cries of “Vandal;” being raised in more than one London paper, until some citizen pointed out that Lincoln was full of remains... It would not be the first time that this has happened, for after William the Conqueror came to Lincoln to inspect the defences of his kingdom a clearance was made of numerous buildings which had been erected upon or within the encircling mounds and moat. Domesday book says that 166 dwellings were thus destroyed on account of the Castle. That must have been something of a clearance!

The whole Castle might well be haunted, for its history is one of bloodshed and cruelty, of attack and defence, of great slaughter, of beatings, hangings, and imprisonments; and enough blood has been shed in and around its walls since the Romans raised them, to fill its moat many times over. Perhaps these times are past, possibly they may never return, and when the obnoxious brick building is cleared away, when the grounds are laid out as ornamental walks, and more great trees have spread their arms; when on summer evenings the citizens of Lincoln walk about and admire the sunset, they may even persuade themselves that such things never happened. But the gaol must be cleared away first.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The Castle Moat’, Lincolnshire Echo, 25 June 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The Castle Moat’, Lincolnshire Echo, 25 June 1914.

5

Continue along Union Road. At Carline Road turn left, and then cross to descend Spring Hill. On the right-hand side, step into Motherby Hill and make your way to its viewing point over the city.

Gilbert lived on Spring Hill in 1914. From there he could view the city, whether in the day or at night. As a countryman, he found the city all lit up a marvel. However, the night-time remained a little disturbing. At the end of the passage, he also hints at his fears of an impending war. Soon the lights would be blacked out!

If the stars are the attraction of the countryside, the lights of a city are equally fascinating. I often walk along the Carline Road on a clear night and watch the twinkling points, dotted here and there, flinging themselves into a line where a road runs, or paling before a blast furnace.

I wonder what Lincoln was like when there were no lights. Until quite recently there must have been only feeble oil lamps in the main streets, and all the winding alleys, all the dark waterside haunts, which are crooked and sinister enough now, must have been really dangerous. There are spots in Lincoln that would lend themselves to dark deeds. I suppose respectable folks stayed indoors after sunset.

That’s the point of course! Until cheap lighting became practicable there was little difference between town and country; by night, at any rate. This cheap light makes the city what it is. It will go ahead, I fancy, and in a generation or so, every path and lane in Lincoln will be as brilliant as the High Street is now.

But there will still be nooks for lovers, and if not the fields around will still abound with couples... Sometimes after eleven I see women staggering towards the slums in the “Draperies,” or coaxing home a quarrelsome or comatose husband. Then I wish there were no street lights, as I hurry past. But it is as well that I should be troubled, and well that I should trouble others, if I can. We are all responsible.

As I walk up Spring Hill I often think I can hear the great animal — the corporate Lincoln — breathing in its sleep. May it continue to slumber peacefully, undisturbed by earthquakes, burglers, or Germans, and awake refreshed again, each morning.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Night in the City’, Lincolnshire Echo, 11 June 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Night in the City’, Lincolnshire Echo, 11 June 1914.

6

Continue down Spring Hill to Hungate, and then to the High Street via St Martin’s Square. Follow the High Street down to the arches of the Stonebow.

Gilbert liked being in the High Street, observing life at all times of day and night. He referred to the Stonebow as an ideal spot, especially for watching people at leisure. He showed a particular appreciation for a local man who served the needs of the passing crowds, and changed his wares and trading hours with the season!

The streets are ablaze with light and liveliness, they throb with interest, for the people are out, the real people: the great army of Lincoln, taking their leisure and enjoying itself in a myriad ways. It is impossible to describe this crowd in detail. I have tried several times, but the impression is all blurred; it is only a moving picture, a memory of innumerable girls and men and boys, with an odd policeman or soldier at intervals. A few faces just out for a second, but no longer...

One of my favourite pastimes, when I first came to Lincoln, was to stand by a chestnut-barrow against the Stonebow between nine and ten at night, and watch the people. There is no better point of vantage on a winter’s night if you have a warm coat, for you are cheered by the glowing cinders and by the fragrance of the roasting nuts...

My particular chestnut man is not very old, but he has travelled and read considerably and knows everyone in Lincoln...

“Do you keep at this trade all year round!”

“Not likely. They’re nearly done now.”

“Done? Why?”

“The spring’s coming and the chestnuts know it.”

“How’s that?”

“I can’t tell you; nobody can; but the nuts know fast enough. They’re hidden in a sack in a cellar, but in a week or two the sap will begin to stir and they’ll be no good for eating”.

A few nights later the stall had vanished. Its owner had retired into the recesses of the city, but the other day I met him again, trundling an ice-cream barrow. Perhaps he is drawn towards barrows, and no other calling appeals to him. “A life that lends itself to meditation,” I mused, thinking that I would like it myself, if I were driven to manual labour; (although writing is nothing else, and very hard labour too, sometimes) but perhaps it isn’t as jolly as it seems.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Night in the City’, Lincolnshire Echo, 11 June 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Night in the City’, Lincolnshire Echo, 11 June 1914.

7

After the Stonebow, turn left to follow Saltergate until you reach Free School Lane. There you will find the Library.

For Gilbert, Lincoln’s new library in Free School Lane was a wonder. He liked its design, unlike certain other public buildings in the city! Gilbert appreciated the benefits that it would bring to local people. He enjoyed watching where people chose to sit in the library, how they behaved, and what they were reading!

Lincoln should be proud of its Public Library, and any citizen who has not been inside should go at once. As a building it is worthy, in my opinion to rank with the older monuments. I have no knowledge of architecture, and can only say if I am pleased or not, mainly in ignorance of how the effect is produced. Some Lincoln buildings cause me great pain, but certainly the Library gives satisfaction...

In the Reference Room sit students with beetling brows, or old gaffers bent on some crank, but it is never full like the Reading Room opposite, where the really interesting people are to be found, and where the comedy of life goes on unceasingly. There is the witty one who hides “Punch” under the cover of his “Sketch,” the persistent one who insists on having it out, and the decided fellow who seizes the “Graphic” and settles down for an hour; indifferent to the hungry eyes all agog for him to stop.

Here is the girl wading down the “Daily Telegraph” for a situation. I always wonder why she is so anxious to change, and I long to ask her, but no talking is allowed; so I turn to watch a schoolboy bolting “Chums;” (how I greedily I once bolted “Chums!”) At the Ladies’ table is much pondering of fashion in papers whose names I never gather. I looked through several of them once, but could find nothing but advertisement. And such advertisements!

Last, but not least, comes the Lending Library. What delighted me here was the system of free access to its books. You no longer have to wander blankly through catalogues, but walk around the shelves and choose for yourself. This of course transforms the whole business. It is not only that it is more convenient, and quicker, and a saving of labour, but that it is an entirely different affair. The rows of books over-shadow you like trees of Wisdom in the Forest of Time.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Civic Pride’, Lincolnshire Echo, 7 May 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Civic Pride’, Lincolnshire Echo, 7 May 1914.

8

Return to Broadgate and cross it once again. Walk down to where the road crosses the River Witham. Take the right-hand pathway along the river, Waterside South, in the direction of the High Street.

Gilbert encountered a large number of ‘tramps’ in Lincoln, many to be traced to some of the poorest quarters of the city, along Waterside. Today, he would be struck by the more recent and smart redevelopment of this area. This said, ‘travellers’ and those in need of ‘temporary abode’ are still to be encountered in the city!

As I walked along the Waterside from the High Street, the water looked oily and stagnant between its stone walls; more like a canal than a river. Every other building seems to be a lodging house, catering for the hundreds of “travellers,” who make this quarter their temporary abode. Each house has something to offer, “Good accommodation for couples” “Good beds for Single Men,” or “Comfortable Lodgings” meet you at every other step, whilst the smaller ones content themselves with a notice written on a piece of cardboard in the window...

And the shops! In one I saw, all together, and all touching, spring onions, oranges, herrings, bars of chocolate, soap, and radishes. You can buy shirts at 4d each, hats for 3d, and patched-up boots at rock-bottom prices... Everything is at the last ebb of cheapness, and is valued not in shillings, but in coppers. The very fish in the shops seem disgusted at their price, and offer up their share to the pervading odour.

It you have old clothes on, you can enter one of these Waterside lodging-houses. You go through a narrow passage and a low doorway to find yourself in a kitchen — a long, low, whitewashed room, in which burns a considerable fire, flanked by kettles of boiling water. The furniture is confined to forms and tables, with a few pictures from the “Mirror of Life” or ‘Police News,” and a couple of gas jets aflare light up the company. But the smell!... Above, are the sleeping apartments for single or married couples. In the former, a long room holds a score of beds, all neat (Lincoln lodging houses are well inspected) and in the latter the couples sleep in tiny cubicles...

You could easily fancy yourself in ancient Lincoln, and I should think that, all things considered, no part of the city has changed less in four or five hundred years. As you emerge into the High Street again you draw a deep breath.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Tramps’, Lincolnshire Echo, 18 June 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Tramps’, Lincolnshire Echo, 18 June 1914.

9

Once back in the High Street, head down towards its junction with Wigford Way and St Mary Street. Cross at the crossroads over to the corner of the site of St Mary le Wigford church.

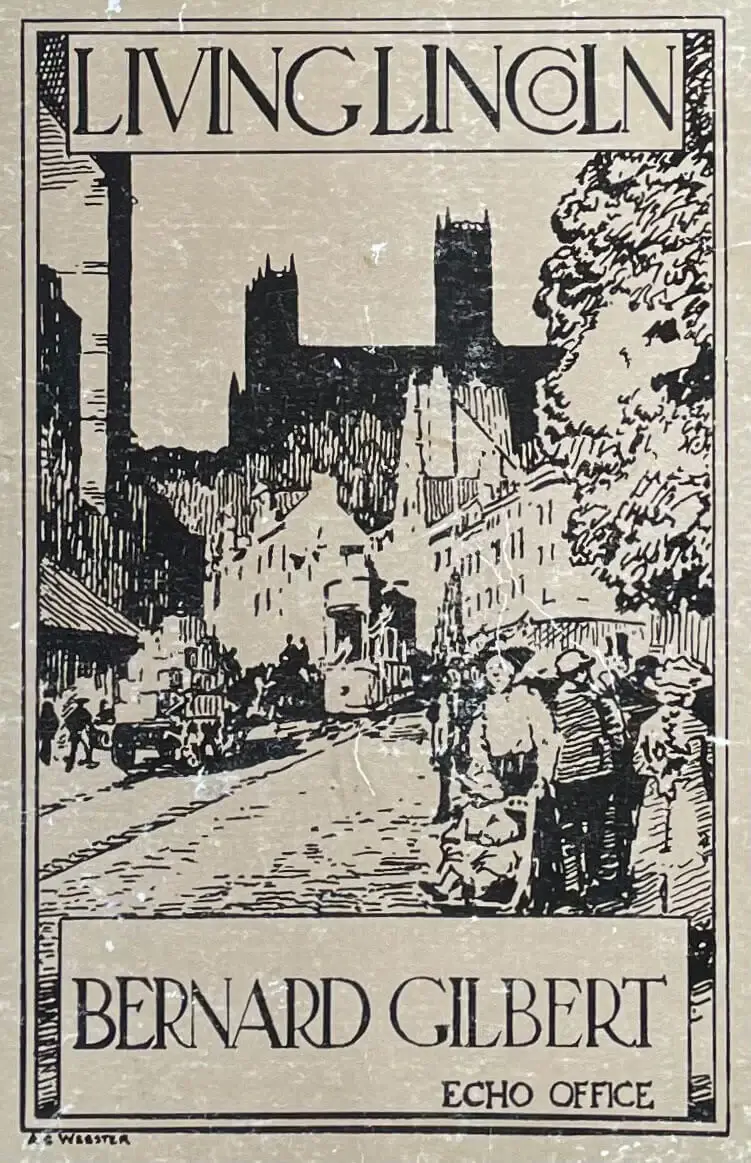

Gilbert’s accounts were soon compiled into a single book. The view chosen for the front-cover image can be seen by standing next to St Mary’s church, looking back up the High Street. You may or may not agree with Gilbert on the qualities of Lincoln’s city life. You may also wonder how much has changed over the last 110 years or so, or not?

What, afterall, is the real difference between town and country life? There can be no hesitation as to the answer. It is the city streets that mark the difference, the life that pulses down these conduits, the human tide passing down these arteries: visible token of sixty thousand people.

To the lover of wild life, of growing things, of birds, trees, and open spaces, the country comes first; to those who desire peace and meditation the village and the open fields with their clouds, their solitude and infinite peacefulness, must come before the city; but to one who desires companionship, and who loves humanity, there can be no comparison. For human nature you must go to the town.

There is always something doing in these streets if you only look. It is, of course, the quality of the looking that counts; the matter of eyes or no-eyes that makes all the difference; for if you have the gift of sight you need never be dull. There is a never-ending show before you, and at every street corner, drama, and tragedy unfold themselves as you pass.

Of course there are degrees, for Lincoln is only just a city. Yesterday it was a small country town... One could soon exhaust its possibilities as against London, whose shops are always fascinating, and whose streets are ever changing, but still, this heap of sixty thousand people affords a sufficiency for the observer. No one ought to be dull in Lincoln.

Streets should be alive and smiling and full of jolly people. A time may come when the crowd palls upon me, when I feel that I must have peace, and I know then that I am old. At present I would not leave them. They are alive, to be busy, to be pleasant, and whilst they remain, may I be there to see.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The City Streets’, Lincolnshire Echo, 21 May 1914; and ‘The City Streets — Continued’, 28 May 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The City Streets’, Lincolnshire Echo, 21 May 1914; and ‘The City Streets — Continued’, 28 May 1914.

10

From the Central Library, or if you are leaving the city centre to the east, you may like to head towards Broadgate. Cross to the other side, and follow Broadgate uphill to its junction with Monks Road. Take this road up to the site where the Lincoln College campus now stands.

Gilbert was fascinated by Lincoln’s Fair, and described it in great detail. It was staged in late April, and located towards the beginning of Monks Road, where the livestock market was also once sited. Gilbert was an enthusiast. Others were not so keen, and were no doubt pleased to see it relocated later, further away from the city centre!

Last Fair-Saturday night I went down in my old clothes, and after half-an-hour’s hard fight, reached the centre of the show ground. Like a drowning man seizing a spar, I clung to a roundabout, and presently hoisted myself up on to its steps into comparative safety. It was a point where three avenues met, and, standing there with one arm braced round the pillar, I surveyed the scene. It was worth seeing! The crowd, like cattle, were jammed hopelessly together; they swarmed in every direction at once like ants. I watched four fellows, whom I knew, aiming up the hill. They went in single file, their arms round each others’ waists (and were stout lads too), but for a long time they made no headway at all, and once, they were swept far aside from their line. Finally I lost them. There seemed to be a hundred organs all roaring together down my neck, drums were banging, bells clanging, and at intervals a steam hooter blew off. It was the apotheosis of uproar.

There was no chance of getting into the side shows, or at least no chance of coming out in one’s original shape, so I contented myself with an occasional ride, wondering what the “Nautch Girls” or the “Fat Lady” were like. Several times I caught the eye of respectable citizens enjoying the fun of the fair, and all of them explained that they were only “looking on.” There must be more physical enjoyment, more actual fun and jollity here than anywhere else in Lincoln at any time. It is idle to estimate numbers, but there was a colossal multitude in and around the ground that night. But everything must be paid for by someone, and those who live near the Fair Ground seem to pay in this instance. Fancy hearing these noises all day and all night, just round the corner! I would rather live on the lower slopes of Vesuvius.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Amusements’, Lincolnshire Echo, 16 July 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Amusements’, Lincolnshire Echo, 16 July 1914.

11

If you are coming into the city from the south, or going out that way, you may like to make your way along the Lower High St. Take a turn at its junction with Scorer St, cross over the Sincil Bank, and follow its course up to the city’s football ground.

Gilbert was a passionate supporter of football in Lincoln, and described in detail one epic encounter. He was gripped by the atmosphere, and graphically recorded the highs and lows. On match days now, you still sense the mood of the fans as they walk towards the game, and with the same hope and expectation!

Is it realised what a hold football has on the people? Lincoln is nearly the smallest city in the Second League, and it has to fight places like Leeds, Leicester, and Bristol – giant cities with giant purses. But none of these support their teams as we do.

We are at once proud and defiant. Sincil Bank is a word of magic and a centre of attraction to more people than all the churches and chapels put together. Something like a quarter of the adult population must crowd down on Saturday afternoon with their sixpences and shillings, and the sport affords them a topic of keen conversation all the week through...

I wish all the superior folk of Lincoln had been at Sincil Bank a few weeks ago when Woolwich Arsenal came down. Lincoln, you must know, went up in the League from bottom to top in 1912-1913; and this season have come from top to bottom... Lincoln , therefore, were wooden poonists as the result of more lost matches than I care to recall, and we – the crowd – were down, too, in the dumps. We still rallied round the gate against hope...

What followed was pure drama. It was art; nothing else. The scene was set. I tried to picture it, but who can picture the passion of ten thousand people? The Lincoln team went mad – sheer mad. They came out of their den like lions and simply ran all over the Redcoats...

Our stand stood up and yelled! We screamed with relief; we shouted, and waved our hats; we hammered with our sticks (I knocked somebody’s hat off; he never noticed), and I am told that we were heard for an immense distance. (This is football). After that, Lincoln scored goal after goal and the whole ten thousand of us never stopped shouting. (I was voiceless for hours afterward.) We got five goals to their two, and completely crushed them.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The Football Crowd’, Lincolnshire Echo, 9 April 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The Football Crowd’, Lincolnshire Echo, 9 April 1914.

12

Alternatively, if you are coming into the city from the west, or going out that way, you may like to leave St Mary le Wigford Church and the High Street, and head along Wigford Way. This will take you along Newland and then to the Carholme and Saxilby Roads. You will eventually reach the West Common and the old Racecourse Stadium.

Gilbert was captivated by the spectacle of race-day on West Common. He pictured the tension in crowds, the speed of the horses, and the roars and the groans of those who had placed a bet. Today, though, the race-days are no more, and you can no longer follow Gilbert, and fall to the temptation of a flutter!

In a dozen years I have only seen three races, and my bets began and ended with putting half a sovereign on Sceptre, when she lost at Lincoln. This must have been a stoke of Providence, for I saw at once how foolish it all was, and vowed never to do it again. The vow was kept for ten years, and it was only by accident that I started once more...

What a democratic sport! How the hope of getting a sovereign for sixpence animates the multitude! Betting on horses may be a hopeless way of earning money, but what a zest it adds to the spectacle as the horses tear home. There’s always a chance, and one win obliterates fifty losses in the memory, if not in the wages...

Silence falls as the numbers go up to show which horses are starters; and then a hum arises as each bookie bellows his offers. The one nearest to me, in a white dustcoat, offered me anything I liked in reason, but I turned from him to see the horses go up. Very fine they looked streaming past, and I studied my race card with feverish glances to find out which was Cuthbert (my secret is out), but it was all Greek – “quarterings and cap reversed” – so I asked a neighbour instead.

The Handicap is run over a straight mile. It isn’t quite straight, but near enough, and it rolls slightly, with a rise, half-way up. It doesn’t look a mile until you notice that the horses at the starting post are mere dancing dots...

A bell tolled, and the next man to me clapped his glasses to his eyes … as the bunch whirled by... Our eyes turned to the board, for you never know; but alas! The fatal number went up, and a 25 to1 chance romped off with the crowd’s money.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The Handicap’, Lincolnshire Echo, 23 April 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘The Handicap’, Lincolnshire Echo, 23 April 1914.

Further reading

For the compilation of Gilbert’s Lincolnshire Echo articles:

Maurice B. Hodson (ed.), Living Lincoln by Bernard Gilbert (Gainsborough, privately printed, 1983).

On Bernard Gilbert’s life and his writings:

Andrew J. H. Jackson, Rural England Through War and Peace: The Literary Work of Lincolnshire’s Bernard Samuel Gilbert, 1882–1927 (Lincoln, History of Lincolnshire, Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 2024).

For detailed local histories of the areas of city described by Gilbert and included in the trail, see: The Survey of Lincoln booklet series (ed. Dr Andrew Walker), especially:

| Monks Road: Lincoln’s East End Through Time (2015). |

| Lincoln’s Castle, Bail and Close (2015). |

| Lincoln’s City Centre: North of the River Witham (2015). |

| Lincoln’s City Centre: South of the River Witham (2016). |

| Pubs in Lincoln: A History (2017). |

| Shops and Shopping in Lincoln: A History (2018). |

| Lincoln's West End Revisited (2022). |

| Lincoln’s Burial Grounds: Commemorating the City’s Dead (2023). |

| Learning in Lincoln: A History of the City's Education Buildings (2024). |

For other information on Bernard Gilbert’s life and work, please contact:

Andrew Jackson

Professor of Local, Regional and Landscape History

Bishop Grosseteste University, Lincoln

andrew.jackson@bishopg.ac.uk

Exchequer Gate

Exchequer Gate

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Outside the Minster’, Lincolnshire Echo, 26 March 1914.

Bernard Gilbert, ‘Outside the Minster’, Lincolnshire Echo, 26 March 1914.